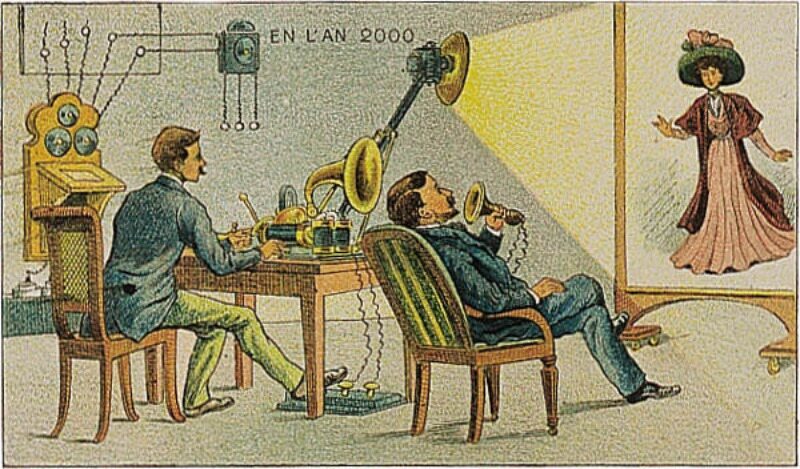

Video conferencing has a long history… much longer as a dream than as a reality; and it is interesting to examine how that dream has evolved.

Teleconferencing by voice goes back to the nineteenth century: Jules Verne’s “The begum’s fortune”, written in 1879, describes a teleconference at the city council of his utopian “France-ville”:

“I will immediately convene the Council!” , said doctor Sarrasin, and preceded his guests to his study. It was a simply furnished room, whose three walls were covered with bookshelves, while the fourth had, below some paintings and objets d’art, an array of numbered devices similar to ear trumpets.

The doctor touched a bell button, which communicated an alert instantly to the homes of all the members of the Council. In less than three minutes, the word “present!” was brought in successively by each wire of communication, announcing that the Council was in session.

This was written three years after Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of the telephone. Bell and others had visionary ideas around two-way visual communications, but an actual commercial “Picturephone” was only introduced by AT&T at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. This had practically no success, despite the inclusion of the system in Kubrick’s iconic space station in “2001: A space odyssey”. Only the arrival of cheap computers and the Internet made video conferencing a commonplace capability.

The vision during the pre-Internet years was all about one to one conversation – a telephone with a video screen. The corporate world stayed out of this dream until the late 1990s, when first efforts at room-to-room video made their appearance. Back then I was a principal engineer at Intel IT, where we were making efforts to integrate Intel’s video conferencing offering into the company’s day to day activity. This was TeamStation, a $10,000 video solution designed for conference rooms. It saw quite limited success: people preferred to stick with telephony.

By 2001 I co-founded with some colleagues the Virtual Collaboration Research Team (VCRT) – a group of Intel IT visionaries that looked ahead at future possibilities for remote teams. A key element in our vision was really good video conferencing; we played with large screens (we even tested a personal pod with a concave wrap-around screen like a satellite dish!), and examined new commercial room-to-room solutions. I particularly remember the Hewlett Packard “Halo” system, which cost well over $100,000 per room and transformed an entire wall into a video screen where you saw the people at the other end in hi-res life-size splendor. Having tested the system, I must say it was a very impressive experience! (You can get a glimpse in this video).

The motivation for testing such expensive solutions was our belief that we had to secure a “Telepresence” experience that is just like “being there”. It was all about the notion that seeing coworkers life size, eye to eye, and in perfect resolution would achieve some elusive quality that is crucial to an effective meeting experience. I remember putting it this way to my team mates: we need to have the same experience that captain Picard had in Star Trek TNG: he’d exclaim “On Screen!” and the alien ship’s captain would spring into view, staring him (malevolently or imploringly, depending on the episode) straight in the eye.

However, with such a high price tag these systems didn’t take over the market by storm. In fact, a colleague pointed out that many of those super video rooms of yesteryear stood unused much of the time; it was too inconvenient to make use of them, making them a “Nice-to-Have”. And here we are, 20 years later, forced by this vile virus to conduct most of our business by video – and it turns out we don’t need the “being there” experience at all! Zoom is a wonderful tool, but it doesn’t even attempt to be a true “Telepresence”. It shows a bunch of tiny images of people sitting, more often than not, in their kitchens and basements, with uneven lighting and all sorts of interruptions from children and cats. And guess what: we manage just fine this way, thank you very much – and at a tiny fraction not only of the cost, but also of the inconvenience of our expensive video room paradigm from 20 years ago: with those rooms you had to pack up and walk over to the room, assuming you had reserved it in advance. Zoom is always a mouse click away.

Which makes me wonder: why were we so far off the mark in believing we need $100K hardware to make remote teamwork work?

Turns out that the whole thing was more exciting than it was really useful. Of course at the time there was no Zoom either; but once Zoom came, which is amazingly easy to use – it is literally easier to start a Zoom meeting than to dial a phone number – it took over. I suppose the problem was that we had no real experience, and assumed that to work well together we must have that “being there” element. We believed that unless people look each other in the eye, they won’t collaborate well. We believed that unless the lighting was perfect, people won’t collaborate well. We believed that unless video quality was perfect, people won’t collaborate well. And COVID19 showed us that we were, simply, wrong.

We’ve found, driven by necessity, that humans are more resilient than we’d thought, and that they’re more eager to collaborate that we could expect. And now we also realize that as long as they sit in individual rooms and not in groups, video quality is immaterial – but that is a subject for another post.

Happy Collaboration!

Nathan –

Another possible reasons for the failure of the Telepresence rooms is the (not great) user experience: Too many times things did not work, did not connect, it was unclear how to work the controls, etc.

I also suspect that unconsciously there was the concern that if this telepresence works well, we will have less business trips… I don’t think anyone down-played the systems with this thought clearly on their mind; but the general aversion and lack of enthusiasm could be related to this.

And while Zoom works well functionally, it really works less effectively in creating friendships and personal engagement. Also: Whiteboarding is still not working well and a lot of situations call for it. So F2F is still important.

Michael

Interesting thoughts, Michael!