Having a hobby you’re passionate about is important. Having a job you’re passionate about is important. And if you’re lucky, there will be a congruence that allows work and hobby to cross-fertilize each other. My hobby of many years is the study of the history of computing technology (you can see some of my collection on my hobby site), and it’s ended up merging with my work. It enriched a number of my lectures – this one, for instance – by providing an unusual treasure of innovative examples; and it led to engagements as curator and scientific consultant for cool museum exhibitions.

This hobby also adds zest to my travel. Last year I was at Bletchley Park, where I got invaluable insight for my work as curator of the Turing Year exhibition at the Jerusalem science museum. This year I’ve just come back from Berlin, where I got close up with the work of an innovator just as interesting as Turing: Konrad Zuse. A visit to an exhibition of his work, guided by Prof. Horst Zuse, Konrad’s son, helped me realize how Zuse’s ground breaking work in the 30’s and 40’s was an early case – the first one, in computing space – of the “garage startup” company model. A comparison to the efforts of US and UK computer pioneers raises some interesting thoughts which I share below.

Presenting the First Computer

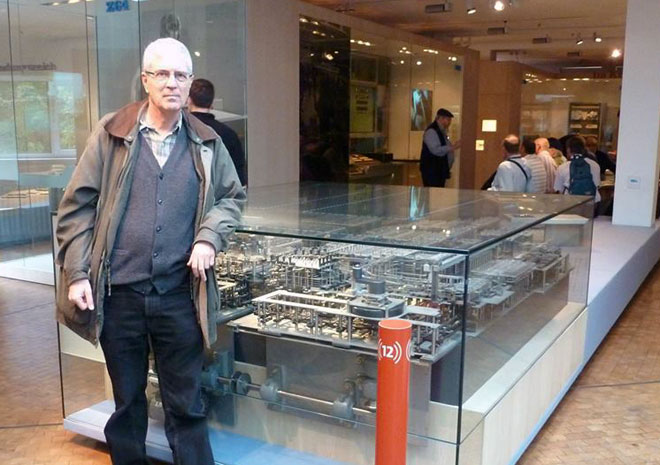

The author next to the rebuilt Z1 computer

Konrad Zuse (1910-1995) graduated in civil engineering in 1935, and when he started to work as a design engineer he grew a dislike to the boring calculations he had to do by hand. Instead of just bitching about this, he decided to develop a machine that could calculate automatically. This was the Z1, whose reconstruction I saw in the Berlin technology museum (the original was destroyed in the bombings of WWII). It was a truly amazing computer, consisting of 30,000 flat sheet metal parts cut by hand with a jigsaw. These plates implement everything – the memory, the CPU logic… an entire computer made from a ton (literally) of interlocking metal parts, and programmed by a punched tape made of 35 mm photographic film stock. Here is an animation showing part of the computer in action.

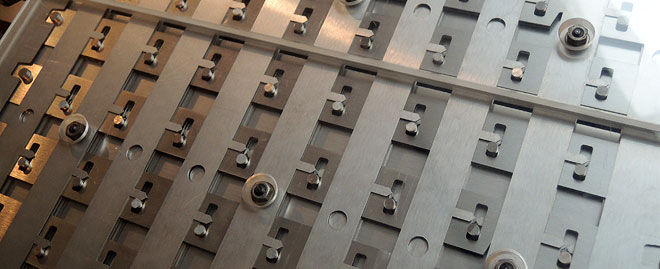

Above: close up on the Z1’s intricate mechanism. Below: Part of the machine’s binary memory bank.

As a curator, what I find ironic is that the Z1 uses as its basic elements the kind of mechanical mechanisms we use in exhibitions to illustrate to kids the concepts of binary logic – we might show one each of the AND, OR and NOT gates, implemented with Plexiglas plates and rods. But Zuse used thousands of these elements – not to explain how a computer works, but to build one that does!

And what a computer he built! The Z1 used Boolean logic and binary floating point numbers. This is what every electronic computer uses today – but in 1938 it was totally, mind-bogglingly innovative. It was also the only digital computer in the world at that time. There are so many candidates for “The First Computer” out there – the ABC, the Colossus, the ENIAC, the Harvard Mark 1… but Zuse’s Z1 and Z3 machines blow them all out of the race. The Z3, in 1941, was without question the first programmable, Turing-complete automatic computer. And although his early machines did not store program instructions in main memory, Zuse also anticipated the stored program concept – normally attributed to Von Neumann in his 1945 EDVAC report – in two patent applications he submitted in 1936. Oh, and he created the world’s first high level programming language, Plankalkül, in 1945.

Presenting the First Computer Startup

Of particular interest is the manner in which the Z1 and its successors were built. Unlike the early computers in the US and the UK, which came about through major projects involving academia, corporations, and lavish military funding, Zuse’s business was a true startup. He spent 2 years building the Z1 in his parents’ living room, using funding from his father, his sister and a few friends, who also pitched in as low-pay laborers to saw those 30,000 metal pieces. Zuse did the entire design from scratch, without access to previous research; and while he did it with a commercial purpose in mind he had no customers lined up. He was driven by a vision, and after the Z1 was done he continued to develop new machines, switching gradually to electromagnetic relays instead of metal plates.

Zuse’s life as an independent entrepreneur was hardly helped by being isolated in a country at war. His first tiny company, Zuse Apparatebau, was destroyed along with his Z1, Z2 and Z3 in the bombing of Berlin, and he barely made it with his family and the Z4 computer to a village where he lacked the electricity to power it. So, what was for some years the only computer in Europe remained crated in a barn, waiting for better days, while Zuse sold woodcuts to feed his family. Yet as soon as conditions changed he regrouped and created a successful new company, Zuse KG, which continued to develop and sell mainframe computers through the 1960’s. A real entrepreneur always keeps trying!

Same goal, two paths: Zuse and Turing

Alan Turing and Konrad Zuse both started their work on computing in their mid-twenties, in 1936 – Turing with his seminal paper “On computable numbers”, and Zuse by starting work on the Z1. They took, however, very different paths.

Turing was a mathematician and a philosopher, and his initial approach to computing was motivated by a desire to understand – at a theoretical level – what is computable and what that means. By contrast, Zuse was an engineer whose primary desire was to develop a useful machine to eliminate the drudgery of calculation – and to produce and sell it. Both converged on the precursors of the computers we know today, but from opposite directions of inquiry. And then there’s the fact that Turing had a deeper quest – a desire to fathom the mystery of how the human brain thinks – which I’m sure Zuse didn’t share.

Another difference is that Turing – who was eager to implement his theories in a practical machine – started later but got there on a faster trajectory. His first design, the Pilot ACE, went operational in 1950 and was based on vacuum tubes and mercury delay line memory while Zuse – despite years of head start – was still making machines using relays and mechanical memory, and working at a clock speed of 40Hz compared to the Pilot ACE’s 1 MHZ. To understand this gap we must keep in mind that the use of vacuum tube electronics on a large scale, while enabling much higher speed, was at the time considered bleeding edge technology of unproven reliability. Turing’s incorporation into the British wartime code-breaking effort, where vast resources were assigned to the development of the tube-based Colossus, exposed him to the feasibility of this technology, whereas Zuse, working in isolation, had rejected proposals to use electronics precisely because he doubted their reliability. Not being an Electrical Engineer must have added to his preference for mechanical systems – Turing wasn’t one either but he was surrounded by many electronics wizards at Bletchley Park.

On the other hand, Zuse did have more of the attributes of the entrepreneur – the intense risk-taking, the inner drive, the willingness to fail and try again. Just think – can you even imagine the sheer courage it took him, to quit his paying job on the faith that he can design a computer – something no human had done before – and then cut by hand 30,000 intricate metal plates and assemble them into a functional device? With no government funding, no academic backing, no assured market… would you be willing to take such a risk? If you would, you may qualify to become a startup founder!

Zuse and Turing never met, and likely never even heard of each other. Yet I wonder, what would happen if there were no war, and they were to get in the same room in 1936? Could they find common ground to discuss their so different approaches to computing? Would they create greater insight together than each could find in isolation? Might they have decided to leverage their different skills, join forces, and become an unbeatable startup founder pair with Zuse as CEO and Turing as CTO?

What would you give to be a fly on the wall of that room?

Related Posts

Alan Turing’s Earthshaking Philosophical Insight

Excellent article.

I recommend you check the third volume of William manchester biography of Churchill as it includes an important section that highlights Turing’s efforts in the war for Britain and the tragic payment he received after almost solving Enigma himself.

I have been and remain a Turing admirer irrespective of his personal life and find it tragic that such a mind and human being was wasted probably at the height of his capabilities. It remains a testament to present efforts to find respect and tolerance albeit not meaning maintaining one’s own beliefs. It’s a matter of being a human being and not a Nazi being.

I really enjoyed reading it. About imagining the possibility of absence of war and pressure, I suggest that at least in Turing’s case, he might had not the adequate facilities and incentive to build a computer in a quick and life-depending manner. So, it might took him more while to reach his accomplishments in a regular environment. However, the future pressures on him, such as condemning him for his sexual orientation were absolute impediments and misfortunes to his work and life.

You may be interested to know that there is some anecdotal evidence suggesting the two of them met after the war.

https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/bitstream/handle/20.500.11850/69357/eth-6960-01.pdf