I was reading the InnovaScapes Institute blog and noticed in the “About Me” sidebar the statement that Chuck House, its author,

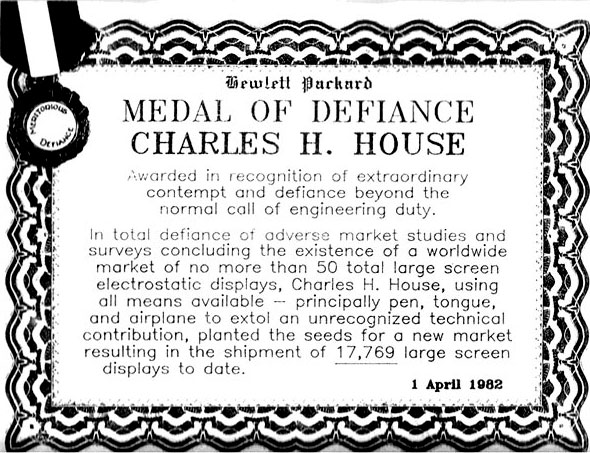

holds HP’s only Medal of Defiance, awarded by David Packard for “extraordinary contempt and defiance beyond the normal call of engineering duty”

This sounded fascinating: a top corporate executive recognizing contempt and defiance – heck, insubordination – as a desirable behavior in an engineer?! Given my interest in promoting Intrapreneurship, my curiosity about this unusual medal was intense.

Fortunately I know Chuck well, having had the honor and delight to collaborate with him when we were both at Intel, so I dropped him a line and asked him to share some insight into this matter, and to allow me to share it with you, my readers. Which he graciously did.

So, here is the story.

The medal

The Medal of Defiance was awarded only once in the history of Hewlett-Packard, by the founder of the company (and then chairman of the board), David Packard. It was presented to Chuck House in April 1982, when he began a new role as HP’s Corporate Engineering Director. Packard had become concerned that the “new HP” in the computer business was becoming very bureaucratic. New CEO John Young thought it key to shift resources from instrumentation to computing, and to co-ordinate all of the R&D efforts across ninety divisions into something much more efficient. But the very appointment of a Corporate Engineering Director was evidence to Packard that a job to co-ordinate strategies, streamline development times, and strengthen productivity rather than emphasize creativity would be viewed as another “Headquarters” imposition.

House was one of those mavericks, though, from a remote division who exemplified local creativity. He had pioneered several major programs, and helped launch a dozen divisions in his first twenty years at the company. If anyone could meet Young’s goals, and persuade the bulk of HP engineers and managers that this was workable, it augured to be House.

Packard recalled the long-forgotten incident with House that is described below, and he concluded that an award to him at inception of this new corporate role could set a tone that emphasized innovation and creativity at every level of the company. Voilà, the Award of Defiance was conceived, created, and bestowed.

The underlying story, in Chuck’s own words

(Extracted from “Old Bribery”, Chapter 2 of Permission Denied: Odyssey of an Intrapreneur, InnovaScapes Institute Press, 2013; available here.)

Given a choice of several new projects, I hadn’t previously seen one that was on the list, an FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) control tower monitor. I asked my boss, “What’s this one?” His cryptic answer: “We don’t really know. It’s a new request, not really an oscilloscope. Milt Russell in our cathode ray tube (CRT) department has worked in this area; he might know something about it.”

The FAA wanted to see images of airplanes near an airport ― recall movie scenes where a control tower is tracking radar blips on CRTs (cathode ray tubes, or television tubes) that indicate planes. Our chief competitor, Tektronix, had voted ‘no,’ giving us an opening. Milt Russell, a short soft-spoken scientist, had come from General Electric, the company that built the display equipment extant at airports. Russell was touting a new technology: an expansion mesh lens that he believed could shorten the picture tube length dramatically (from 54 inches to 18 inches).

For this project, however, there was a new requirement: the FAA wanted the CRT to show more than a radar blip. They wanted identifying flight letters next to each blip, a hard goal with an expansion mesh approach. The prototype didn’t meet the FAA needs since it defocused the letters that identified the planes. Russell fiddled with the focusing problem; I sought applications where focus wasn’t so important. We probably should have gone back to our bosses and said, “Hey, this won’t work for the FAA requirement. We should call FAA and say ‘we’re sorry’ and then cancel the project.”

The prototype was pretty intriguing. Essentially it was a very high-speed television set. The diagonal screen size was impressive for a ‘scope, 14 inches instead of 5 ― an 800 per cent larger display. The joke was that we were building a much faster TV set so that you could watch the movie Gandhi in four minutes. Other wags opined that it was a ‘scope for nearsighted long-armed engineers.

By the time that our bosses figured out that we couldn’t solve the FAA problem, I loved the pictures we could display. Wanting to take the unit to some potential customers, I was strongly told ‘No.’ HP did not allow engineers to go alone to customers (a sales representative had to go); second, we couldn’t afford the extra travel expense; and third, HP didn’t allow prototypes to be shown to customers because that might tip our hand.

I proposed to take the box with me on a personal trip to California for the upcoming Christmas holidays, calling on customers where HP sales people set up the meeting. This met two of the three objections ― the contacts and the travel cost. For the third point, I argued that if we were going to cancel the project for lack of market, there was no real danger in ‘tipping our hand to competitors’. They grudgingly acquiesced.

The box, though, was too big to put in my car. I had to package the unit ― in an eight cubic foot box, two feet on every side ― take it to the airport, and fly it from place to place. At each stop, I’d put my family in a motel, take the right front seat out of my vintage Volkswagen Beetle, go to the airport, get the box, bring it to the motel, unpack it, and then go to the customer.

I met with twenty potential customers in two weeks. It generated phenomenal excitement. Sadly, the findings weren’t persuasive back home. At the annual division review, Packard asked us about the technology, and later, about the market. The executives punted, saying they’d found few potential customers. I wasn’t asked ― I was ‘just’ a designer, sans experience with marketing. In a stentorian voice, Packard said: “When I come back next year, I don’t want to see this project in the lab.”

Told this verdict the next day, I was quite upset. Our marketing manager, a talented, energetic voluble man, had said the sales forecast was thirty-one units, a number that enraged me. I countered, saying that he’d missed by six percent, since he had not called my father, who wanted two units.

I argued for the applications; my R&D boss was courageous, granting an extra $60,000 for eight months to get to production. When Packard returned a year later and saw it, he nearly had a stroke ― pounding the table, he bellowed : “I thought I said to kill this damn thing.”

I witlessly said, “No, sir. You said when you came back, you didn’t want to see this in the lab. It isn’t. It’s in production.”

The answer didn’t satisfy.

HP1300A monitor in use

Results: Most paradigm shifts start slowly. Three months after sales release, we had sold forty units, a pleasing if not rousing launch. The new applications for this display box were compelling. It became the first commercially available computer graphics CRT. Beyond Alan Kay’s ‘personal computer’, Doug Engelbart bought one to experiment in the first demonstrated computer network in the famous “Mother of All Demos”. It won a Hollywood Oscar for technical screen graphics, it was the surgery room display for Dr. Norman DeBakey’s first artificial heart transplant, and it was the basis for the TV space video of Neil Armstrong’s foot landing on the moon July 20, 1969. Seventeen thousand large-screen display units ultimately sold, for thirty-five million dollars. Development costs were a pittance, less than three hundred thousand dollars. Profits were in excess of six million dollars.

These high-visibility successes though were in the future – for the moment all we had were a few sales and a peeved CEO.

What did I learn? Bring passion and dedication to your job, and never quit in the face of adversity. Be willing to challenge ‘the rules’ – nothing good happens unless something happens first.

Some concluding thoughts

Chuck’s fascinating success story of driving intrapreneurship against corporate resistance is well told, so I won’t elaborate on it. I’ll only share some thoughts it brings to mind:

- Note that “Packard had become concerned that the ‘new HP’ in the computer business was becoming very bureaucratic”. Kudos to David Packard (not that he needs my endorsement, with the track record he has): not every executive is worried about bureaucracy. The smart ones do, otherwise they will eventually (but much too slowly) drive their company to the ground. Large companies must perforce have a bureaucracy level absent in a startup, but the better ones take steps to keep it in check by encouraging innovation and a measure of non-conformism.

- Keep in mind that it’s all too easy to hand out a medal for a success that netted the company millions. What’s no less important is that it be safe to take risks while knowing that many of them will fail, as many of them are bound to do.

- Above all, you (as a manager) need to do a masterful juggling act: you have to balance innovation and planning, discipline and defiance, empowering your innovators yet not throwing good money after bad… all in an ever-changing business landscape. Keeping the baby without the bath water can get challenging, but is crucial (in case you wondered why successful managers get a hefty pay… it’s not easy!)(in case you wondered why successful managers get a hefty pay… it’s not easy!)

Related posts

New Insight Article: Intrapreneurship – How to Do It and Live to Tell the Tale

Chuck House reflects on this post, and shares another amazing story of intrapreneurship from our shared past at Intel, at http://intrapreneuringinnovation.blogspot.co.il/2013/05/hijacking-summit.html